Vladimir

Kroupnik

END OF "TIRPITZ"

The historians of RAAF till now

proudly note that Australian airmen took part in sinking of the biggest ship

of Kriegsmarine. Some of them visited Russia in 1944 in the ranks of an air

group which successfully bombed the mighty battleship from a Soviet base

Yagodnik. A piece of a Russian historian M.N. Suprun was a base for this

page. The author of the site made some additions and wants to express his

gratitude to Igor Gostev (Archangelsk, Russia) for his great help in collecting

of data for this page. In the beginning of it - picture of an English artist

Frank Wootton "Sinking of Tirpitz" (Royal

Air Force Benevolent Fund)

The historians of RAAF till now

proudly note that Australian airmen took part in sinking of the biggest ship

of Kriegsmarine. Some of them visited Russia in 1944 in the ranks of an air

group which successfully bombed the mighty battleship from a Soviet base

Yagodnik. A piece of a Russian historian M.N. Suprun was a base for this

page. The author of the site made some additions and wants to express his

gratitude to Igor Gostev (Archangelsk, Russia) for his great help in collecting

of data for this page. In the beginning of it - picture of an English artist

Frank Wootton "Sinking of Tirpitz" (Royal

Air Force Benevolent Fund)

In the end of 1943 the British Admiralty

found out that the Germans wee preparing a major naval operation with participation

of battleship. Under an agreement with the Soviet command the 543rd air reconnaissance

group, consisting of three "Photospitfires", moved to the Vaenga-1 air base

in order to enhance surveillance over "Tirpitz". The Spitfires conducted

50 sorties from Soviet air strips in September-November 1943, having done

reconnaissance over the main German naval bases in Northern Norway. Due to

these flights it became possible to warn the Allied headquarters about the

sortie of a German squadron led by "Tirpitz" on the 7th of September. Information

about an operation targeted at destruction of Allied bases on Spitzbergen

was fully confirmed. The British reconnaissance pilots kept their eyes on

the squadron during the whole sortie. Possibly, that's why the Kriegsmarine

command ws made complete the operation before time. In 1943 all aircraft

of the reconnaissance group were handed over to the 18th reconnaissance regiment

of the Northern Fleet Air Force, and the British pilots returned home.

Sending convoys to the Northern Russian

seaports, the British Admiralty feared not without a ground, that they would

become a prey for the Kriegsmarine surface ships. The Royal Navy prepared

an operation on annihilation of "Tirpitz' by an air strike from an aircraft

carrier (operation "Tungsten"). In this connection a group of Spitfires was

moved again to Vaenga-1 in March 1944 to enhance surveillance over "Tirpitz".

The British pilots regularly informed the English mission and the Northern

Fleet headquarters about all movements of German ships. It ws their merit

that in March 1944 after a strike from an aircraft carrier the best ship

of Kriegsmarine was put out of action for four months. The pilots which had

visited Russia, were allowed to wear souvenir Soviet stars along with their

battle awards, and the pilots were very much proud of it. As before, all

planes were handed over to the 118th Soviet air regiment in the end of May

upon the returning of the airmen to Great Britain.

|

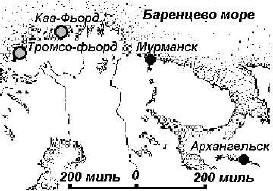

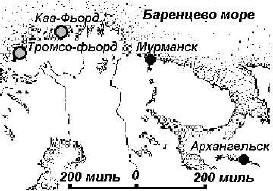

A schematic map of the area of combat activities of the

617th and 9th squadrons of RAAF in September-November 1944 (Archangelsk in

the right bottom corner, Kaa-fjord straight below the top in the left corner

and Tromso-fjord is south-west of it)

|

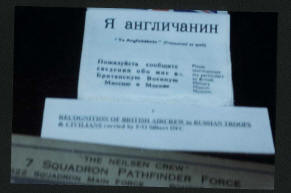

Such badges were worn by British and australian airmen,

which flew over the Soviet territory, in case of an unplanned landing and

encounter with Soviet people:

ß - àíãëè÷àíèí. Ïîæàëóéñòà ñîîáùèòå îáî

ìíå â Áðèòàíñêóþ Âîåííóþ Ìèññèþ â Ìîñêâå (I am an Englishman. Please, inform

the British Military Mission in Moscow about me).

(Author's photo from the RAAF museum in Perth, WA)

|

In September 1944 a new operation on

annihilation of "Tirpitz" was designed (operation "Paravan"). The base of

the German battleship was then out of reach of the Lancaster bombers based

in the North of Great Britain. The German justifiably expected a strike from

north-west and because of it a sudden attack from this direction wouldn't

have been feasible. The RAF Command addressed to the Soviet leadership to

provide an air strip in the Soviet North to conduct a sudden strike on the

german battleship from the south. An appropriate agreement was quickly concluded.

The best bombers units of RAF: the 9th

and 617th Lancaster squadrons were selected for this operation. A photo reconnaissance

plane "Mosquito" from the 540th squadron and two Liberators were also included

into the air group for transportation of technical personnel. The Lancaster

carried super powerful bombs "Tallboys" 12,000 pounds (more than 5t) each.

All airmen of the group had made not less than 60 sorties over the German

territory and had battle awards. One more Lancaster from the 463rd squadron

was included into the group - it had a documentary operators intending to

film the oncoming attack on the mightiest battleship of Kriegsmarine...

On the 11th of September at 21.41 p.m.

the aircraft took off from their air base in Scotland and headed towards Archangelsk.

They were being waited for there. A steamship "I. Kaliayev" (on board of

which airmen of the 151st RAF air wing lived in 1941) had been moved to the

Yagodnik air base for accommodation of the British. Two dugouts for 50 men

each were also built. When it became known that 40 planes instead of 30 would

arrive with passengers as well (all up 334 men), two more dugouts were built

over one day. two cutters and two single engine planes were also allocated

for the british to provide them with communications with town.

On the 12th of September at 6 a.m.

a first lancaster of captain Prier turned out over Yagodnik. The pilot headed

towards the radio station immediately after landing. The Lancasters were

landing blindly, with no two way coordination, because of bad weather conditions

and mismatch between the call sign frequencies of a Soviet and british radio

transmitters. That's why only 31 out of 41 aircraft landed in Yagodnik. Soon

it became known that two planes had landed in Kegostrov, two - in Vaskov,

two - in Onega. One plane landed on each of air strips in Belomorsk, Molotovsk,

Chumbalo-Navoloka and Talagy. All these aircraft required small repairs.

fortunately, none of the airmen was seriously injured. The crew of lieutenant

Killy, which landed in a swamp near the Talagy village, was the unluckiest.

A paratrooper guide, who led the crew to a river where a hydroplane was waiting

for them, had to be landed nearby. Four Lancasters flew over to Yagodnik

some hours later. Six remained on the places of landing.

The airmen spent their first day on

the Russian soil on preparation of the aircraft to the operation, on search

of lost crews and securing of bombs thrown by Lancasters near Molotovsk and

Lapominky during forced landing. On the 13th of September the hosts decided

to get familiarized with unknown to them "best English machines". The Soviet

engines and technicians highly appraised the English bombers. Each of them

who was scrutinizing the machines, compiled a detailed report on the observed

for the intelligence department of headquarters. The main attention in the

reports was paid to a "secret" bomb-sight of unknown design, a modernized

astrograph, which was able to estimate automatically a plane's position,

plotting it on sliding film and navigator's map. The Soviet technical personnel

didn't miss out two locators and a small hatch on the right hand side of

the front cockpit. They managed to reveal that it was designed for casting

of foil neutralizing enemy locators. Despite weak protests of the English

side, the Soviet aviators discovered a lot more of interesting and educating

for themselves.

The operation planned for the 14th of

September, was postponed for a day by the British Command. The squadron commanders

were busy specifying the flight route along with the Soviet staff officers.

The crew members were having a rest. An international soccer game took place

that day. Two colonels were amongst the players - chief of headquarters of

the Northern Fleet Air Force Loginov and the commander of the british air

group MacMullen. A military brass arrived to the soccer field and played

a march after each goal. The guests lost 0:6 but were not upset. "Today we

have understood how strong is the foe of the Germans on the Russian front,

- one of the English players said. - Tomorrow they will find out what the

british airmen are capable of".

The 15th of September arrived. Strictly

to the plan at 4.37 a.m. the "Mosquito" reconnaissance plane took off to assess

the weather conditions in the target area. The skies over the Kaa-fjord were

clear. The airmen were in a good mood: each of them considered it as a must

to do a contour flight over the deck of "I. Kaliayev" - their Russian home.

Everybody was so sure of success that there was no fighter cover...

At 10.00 a.m. the Lancasters set their

course and at 3.57 p.m. they were over the target. The enemy AA guns kept

silent. Suddenly one of the planes, which was flying let of the flag one,

left the formation and headed towards "Tirpitz". The flight order was broken

and the flight leader lieutenant colonel Tait had to lead the group for another

circle. The surprise factor was lost. It took the enemy two minutes to set

up a smoke screen with a help of special pipeline circling the fjord. Nevertheless,

the mast tops of "Tirpitz' were still seen and the british attacked the battleship

having thrown about 90 tons of bombs. One straight hit on the bow part of

the ship was achieved and, apart from it, the hull of the ship wa damaged

by explosions of bombs which had fallen next to it. At 4.04 p.m. The aircraft

set a return course and in three hours landed with no losses.

Several Australians took part

in this attack - and amongst them a pilot Carey of the 617th squadron whose

plane ws damaged by enemy flak. The only hit on "Tirpitz' was noticed by

an Australian, fight lieutenant Buckham who ws flying the filming crew plane.

he was the only pilot who after the attack led his plane to the Waddington

base in Scotland. Most of his flight was just above the sea in very poor

weather conditions. The flight time from Yagodnik to Waddington made up 14

hours 33 minutes - an absolute record for Lancasters.

Several Australians took part

in this attack - and amongst them a pilot Carey of the 617th squadron whose

plane ws damaged by enemy flak. The only hit on "Tirpitz' was noticed by

an Australian, fight lieutenant Buckham who ws flying the filming crew plane.

he was the only pilot who after the attack led his plane to the Waddington

base in Scotland. Most of his flight was just above the sea in very poor

weather conditions. The flight time from Yagodnik to Waddington made up 14

hours 33 minutes - an absolute record for Lancasters.

|

"Tirpitz" in its better times*

|

The "Mosquito" reconnaissance plane

pilot was so sure that the bombs had missed the target that he even didn't

bother about photography of "Tirpitz". Nobody could confidently say if there

had been a hit. A British reconnaissance plane, having made a sortie over

the Kaa-fjord several days after, failed to locate the battleship. soon after

that the British Intelligence received a radio transmission from a Norwegian

patriot Lindberg who lived in the town of Tromso: "Tirpitz" has arrived in

Tromso, there is a large hole in the bow part of the deck". Five days after

the attack a British reconnaissance plane managed to photograph the results

of bombing. based on the intelligence from Norway and photographs, specialists

estimated that repairs of "Tirpitz" will take at least 9 months. The "Paravan"

operation ended successfully.

The planes began to leave Archangelsk.

On the 7th of September at 10 p.m. a ceremony farewell was given to the last

two leaving planes. the results of bombing had become known by that time

and the airmen were leaving with a feeling of done duty. Six damaged Lancasters

were handed over to the Soviet side without compensation, two of them were

repaired in Kegostrov and later used in transport and reconnaissance aviation...

"Tirpitz" had to move further south

into the Tromso-fjord because of fear of new attacks from Yagodnik. The ship

couldn't move faster than 6 knots and, practically, couldn't make an open

sea anymore. the repairs could be made only in Germany. The German Command

decided to place "Tirpitz' in shallow waters to prevent its sinking. Dredges

began to build dams around the unmoving battleship. Simultaneously about

500 of crew members of the engine compartment were transferred on shore...

The RAF command encountered another

problem - flying conditions over the Tromso-fjord lasted for not more than

a day a week. Nevertheless, the battleship was within a reach of Lancasters

of the 5th air group from air-strips in Scotland. However, more powerful Merlin-24

engines and additional fuel tanks were installed on them. On the 29th of

October a reconnaissance plane transmitted that the weather over the Tromso-fjord

was improving, and 38 Lancasters of the 9th and 617th squadrons took off.

This time heavy clouds filled the fjord half a minute before the attack

and didn't allow an aimed bombing. One Lancaster was seriously damaged by

AA fire during this attack and had to land in Sweden.

On the 12th of November the same squadrons

at last approached the fjord in clear weather. Australian pilots Kell, Ross,

Sayers and Lee took part in the attack. 29 tallboys were thrown. Several

straight hits decided the fate of "Tirpitz" - the battleship began to list

to the port side and in 10 minute after the attack turned over. In two hours

a reconnaissance plane transmitted that only the ship's bottom was seen above

the water. Australian airman Buckham managed to photograph damaged and listing

"Tirpitz" through the smoke screen and smoke of bomb explosions. Thus the

best ship of Kriegsmarine ended her career.

On the 12th of November the same squadrons

at last approached the fjord in clear weather. Australian pilots Kell, Ross,

Sayers and Lee took part in the attack. 29 tallboys were thrown. Several

straight hits decided the fate of "Tirpitz" - the battleship began to list

to the port side and in 10 minute after the attack turned over. In two hours

a reconnaissance plane transmitted that only the ship's bottom was seen above

the water. Australian airman Buckham managed to photograph damaged and listing

"Tirpitz" through the smoke screen and smoke of bomb explosions. Thus the

best ship of Kriegsmarine ended her career.

|

Bottom of "Tirpitz' is seen above the water

|

* Pictures of "Tirpitz" were taken from web-site Ship Photoes

M.N. Suprun. Britanskiye Korolevskiye

VVS v Rossii, 1941-1945. (Iz sbornika "Severnye konvoi: issledovaniya, vospominaniya,

documety". Vyp.2. – M.: Nauka, 1994)

D. Woodward. Tirpitz. 1953

J. Herrington. Australia in the War of

1939-1945. Air Power Over Europe. 1944-1945. 1963

A. Preston. Battleships. 1981

Back

to contents

The historians of RAAF till now

proudly note that Australian airmen took part in sinking of the biggest ship

of Kriegsmarine. Some of them visited Russia in 1944 in the ranks of an air

group which successfully bombed the mighty battleship from a Soviet base

Yagodnik. A piece of a Russian historian M.N. Suprun was a base for this

page. The author of the site made some additions and wants to express his

gratitude to Igor Gostev (Archangelsk, Russia) for his great help in collecting

of data for this page. In the beginning of it - picture of an English artist

Frank Wootton "Sinking of Tirpitz" (Royal

Air Force Benevolent Fund)

The historians of RAAF till now

proudly note that Australian airmen took part in sinking of the biggest ship

of Kriegsmarine. Some of them visited Russia in 1944 in the ranks of an air

group which successfully bombed the mighty battleship from a Soviet base

Yagodnik. A piece of a Russian historian M.N. Suprun was a base for this

page. The author of the site made some additions and wants to express his

gratitude to Igor Gostev (Archangelsk, Russia) for his great help in collecting

of data for this page. In the beginning of it - picture of an English artist

Frank Wootton "Sinking of Tirpitz" (Royal

Air Force Benevolent Fund)

Several Australians took part

in this attack - and amongst them a pilot Carey of the 617th squadron whose

plane ws damaged by enemy flak. The only hit on "Tirpitz' was noticed by

an Australian, fight lieutenant Buckham who ws flying the filming crew plane.

he was the only pilot who after the attack led his plane to the Waddington

base in Scotland. Most of his flight was just above the sea in very poor

weather conditions. The flight time from Yagodnik to Waddington made up 14

hours 33 minutes - an absolute record for Lancasters.

Several Australians took part

in this attack - and amongst them a pilot Carey of the 617th squadron whose

plane ws damaged by enemy flak. The only hit on "Tirpitz' was noticed by

an Australian, fight lieutenant Buckham who ws flying the filming crew plane.

he was the only pilot who after the attack led his plane to the Waddington

base in Scotland. Most of his flight was just above the sea in very poor

weather conditions. The flight time from Yagodnik to Waddington made up 14

hours 33 minutes - an absolute record for Lancasters.  On the 12th of November the same squadrons

at last approached the fjord in clear weather. Australian pilots Kell, Ross,

Sayers and Lee took part in the attack. 29 tallboys were thrown. Several

straight hits decided the fate of "Tirpitz" - the battleship began to list

to the port side and in 10 minute after the attack turned over. In two hours

a reconnaissance plane transmitted that only the ship's bottom was seen above

the water. Australian airman Buckham managed to photograph damaged and listing

"Tirpitz" through the smoke screen and smoke of bomb explosions. Thus the

best ship of Kriegsmarine ended her career.

On the 12th of November the same squadrons

at last approached the fjord in clear weather. Australian pilots Kell, Ross,

Sayers and Lee took part in the attack. 29 tallboys were thrown. Several

straight hits decided the fate of "Tirpitz" - the battleship began to list

to the port side and in 10 minute after the attack turned over. In two hours

a reconnaissance plane transmitted that only the ship's bottom was seen above

the water. Australian airman Buckham managed to photograph damaged and listing

"Tirpitz" through the smoke screen and smoke of bomb explosions. Thus the

best ship of Kriegsmarine ended her career.