Vladimir

Kroupnik

INCREDIBLE ADVENTURE

OF THE RUSSIAN AIRMAN IVAN SMIRNOFF IN AUSTRALIA

On 3 March 1942 Lieutenant Zanhiro

Mayanobo – the commander of a Japanese squadron of "Zero" fighters, based

on the Timor Island, attacked the town of Broome (Western Australia). Simultaneously

with it 8 Japanese planes bombed the town of Wyndham in the NE of Western

Australia.

The day before the attack there were

three hydroplanes in the haven of Broome and several aircraft on the small

town airdrome. On the day of the attack 16 hydroplanes and a schooner stayed

in the haven waiting for boarding of refugees from the Island of Java and

other areas of Indonesia and Indo-China.

At 9.30 a.m. the crew of a "Quantas

" hydroplane was preparing to receive passengers when everybody noticed

on the horizon approaching planes of unknown nationality. And only when

the Japanese planes began to strafe the hydroplane with bullets and bomb

them everything became clear. Fuel drums caught fire and began to explode,

three hydroplanes immediately sank, the whole haven was set ablaze and

covered by smoke. Panic spread among the passengers.

Captain Lester Brain – a "Quantas"

pilot - was in his office when he heard explosions and bursts of machine-gun

fire. When he had run to the shore he saw as a "Quantas" hydroplane exploded

from a straight bomb hit and many of the passengers, including women and

children, died… Having encountered no opposition the Japanese pilots descended

nearly to the water. Lieutenant Winkel (a Dutchman) took a machine gun

from a transport aircraft "Lodestar" and, having leaped outside, opened

fire at an approaching Japanese plane, which exploded and fell into the

sea… The attack lasted for more than an hour, and during it the Japanese

wiped out all 16 hydroplanes in the haven and 6 panes in the town airport.

77 Australian had been buried by night.

It remained unknown how many Dutch refugees had died as many of them had

perished in the burnt airplanes or drowned. Corpses were come across in

the coastline mangro bushes for quite a while after the attack. Several

days after the wounded and the refugees were sent to Perth.

Commander of a transport aircraft

DC3 (Douglas) of the Dutch Air Force Captain Ivan Vasilievich Smirnoff

(on the photo to the left – he during WWI) became an unwilling participant

of this episode. He was born on 30 January 1895 on a farm near the town

of Vladimir (Russia) in the family of a well-off peasant cattle greaser

and wheat grower. Ivan was interested in mechanics from an early age, liked

to maintain and repair agricultural machinery which belonged to his family.

His father wanted him to enter the Moscow University to study engineering,

but, when the WWI had broken out Ivan escaped to the front with two mates,

joined the army voluntarily and was enlisted into the 96th Omsk

regiment. He distinguished himself in the infantry and at the age of 19

was awarded with the St George Cross. After being wounded into the leg

he got his bone damaged to the point when the surgeons wanted to amputate

his leg, but he refused and was placed into a hospital situated next to

an airfield. After recovery from the wound he applied for acceptance to

the aviation school, finished it and was accepted in the 19th

squadron led by the most famous Russian ace of the WWI – shtabs-kapitan

(staff-captain) Alexander Kazakov. Smirnoff shot down 12 German aircraft

(the last – on 10 November 1917)? And as to the number of battle awards

had become the second in the Russian Imperial Air Fleet. Amongst his awards

(beside the Soldier’s St George Cross) there were the Officer’s St George

Cross, Gold Saber, Orders of St Anne, St Stanislaus, St Vladimir with Swords,

White Eagle. In 1917 together with his friend Login Lirsky Smirnoff fled

to England where he joined the RAF. He, a former ensign of the Russian

Army, served here as a flying instructor in the rank of major. After the

Armistice he was demobilized and during the Civil War in Russia he served

as the White Army General Denikin’s attaché in France.

Commander of a transport aircraft

DC3 (Douglas) of the Dutch Air Force Captain Ivan Vasilievich Smirnoff

(on the photo to the left – he during WWI) became an unwilling participant

of this episode. He was born on 30 January 1895 on a farm near the town

of Vladimir (Russia) in the family of a well-off peasant cattle greaser

and wheat grower. Ivan was interested in mechanics from an early age, liked

to maintain and repair agricultural machinery which belonged to his family.

His father wanted him to enter the Moscow University to study engineering,

but, when the WWI had broken out Ivan escaped to the front with two mates,

joined the army voluntarily and was enlisted into the 96th Omsk

regiment. He distinguished himself in the infantry and at the age of 19

was awarded with the St George Cross. After being wounded into the leg

he got his bone damaged to the point when the surgeons wanted to amputate

his leg, but he refused and was placed into a hospital situated next to

an airfield. After recovery from the wound he applied for acceptance to

the aviation school, finished it and was accepted in the 19th

squadron led by the most famous Russian ace of the WWI – shtabs-kapitan

(staff-captain) Alexander Kazakov. Smirnoff shot down 12 German aircraft

(the last – on 10 November 1917)? And as to the number of battle awards

had become the second in the Russian Imperial Air Fleet. Amongst his awards

(beside the Soldier’s St George Cross) there were the Officer’s St George

Cross, Gold Saber, Orders of St Anne, St Stanislaus, St Vladimir with Swords,

White Eagle. In 1917 together with his friend Login Lirsky Smirnoff fled

to England where he joined the RAF. He, a former ensign of the Russian

Army, served here as a flying instructor in the rank of major. After the

Armistice he was demobilized and during the Civil War in Russia he served

as the White Army General Denikin’s attaché in France.

After the Civil War in Russia Smirnoff

managed to find a job in the Belgian air company SNETA, then, in 1922 he

began to fly for the Dutch company KLM. During his stay in Copenhagen he

met a Dutch actress Margo Linnet and married her in 1925. In 1929 he was

granted Dutch citizenship and several years after for his contribution

to the development of the Dutch aviation awarded an order which he received

from the Queen Wilhelmina herself.

In 1940, because of the war, Smirnoff

moved to Batavia (Now Jakarta). After the Pearl-Harbor attack and the beginning

of war in the Pacific Smirnoff joined the Dutch Air Force (where he was

nicknamed "Turk") (on the photo to the left – Smirnoff in the uniform

of the Dutch AF). His main task was to evacuate civilians to Australia.

Just before one of these flights, at 1 a.m. 2 March 1942 an official got

on his plane and handed him a parcel with the following words: "Take care

of this parcel! You will hand it to the Commonwealth bank in Melbourne."

The small box was wrapped in brown paper and bound with cord sealed with

wax. There were no documents or instructions enclosed. Smirnoff took the

parcel and put it into an aluminum safe, having paid no attention to it.

In 1940, because of the war, Smirnoff

moved to Batavia (Now Jakarta). After the Pearl-Harbor attack and the beginning

of war in the Pacific Smirnoff joined the Dutch Air Force (where he was

nicknamed "Turk") (on the photo to the left – Smirnoff in the uniform

of the Dutch AF). His main task was to evacuate civilians to Australia.

Just before one of these flights, at 1 a.m. 2 March 1942 an official got

on his plane and handed him a parcel with the following words: "Take care

of this parcel! You will hand it to the Commonwealth bank in Melbourne."

The small box was wrapped in brown paper and bound with cord sealed with

wax. There were no documents or instructions enclosed. Smirnoff took the

parcel and put it into an aluminum safe, having paid no attention to it.

Cannon salvos were already heard. (Batavia

was taken by the Japanese three days after). Apart from Smirnoff there

were second pilot Johan Hoffman, mechanic, radio-operator, Dutch airmen,

KLM servicemen, a woman (Mrs. Van Tuyn with a child) on board of his plane.

The Douglas had no passenger seats and the woman with her child was placed

on the second pilot’s seat. Others sat on the floor. When only 80km of

the route to Broome left, the Douglas was attacked by the Japanese fighters.

It was a trio of fighters which did not participate directly in the attack

on Broome, but which was covering the attacking "Zero" fighters from above

at a significant altitude. Thus, Smirnoff had come across these three fighters

o their way back to Timor. The "Zero" fighters were led by Lieutenant Zenziro

Miyano (he was in charge of the attack on Broome, later became an ace with

16 downed planes on his account, shot down and died over Guadalkanal on

16 June 1943), sergeant Takashi Kurano and private Zempey Matsumoto.

Machine-gun bursts began to hit the

Douglas. Four shells wounded the Russian pilot – two into the left hand,

one into the right and one into the left hip. Soon throw the glass of his

cockpit he saw smoke on the horizon – that was fire over Broome. After

another attack the Japanese set ablaze one of the Douglas’s engines and

Smirnoff dived with no hesitation. He landed on sandy beach next to the

surf line and managed to have the fire on his plane extinguished.

A year after the incident, another

passenger, Dutch pilot Lieutenant Peter Cramerus, described his ordeal

to an American newspaper reporter:-

"At Bandung I was ordered to go to

a flying school in Australia by the next plane. This was a DC3 piloted

by Commander Smirnoff, a Russian-born naturalized Dutch citizen. Just as

we reached Australia, after daybreak, three Japanese fighters flying back

from Broome sighted us. Smirnoff put up the greatest show of flying anybody

in the world will ever see, coming down in a tight spiral and making a

crash-landing on the beach."

"When the port engine suddenly burst

into flames the immediate fear was that the fire would spread to the fuel

tanks and cause an explosion. Equally hazardous was the possibility of

it causing an in-flight structural failure of the wing. Ivan elected for

a hasty beach landing below. As the Douglas rolled to a stop, he skillfully

swung the nose into the edge of the surf, at the same time effectively

dousing the burning engine."

The Zeroes began to strafe the crush

landed Douglas with machine guns. The KLM mechanic Joop Blaauw was wounded

by them in two legs. Having ordered everybody to get off the plane the

Russian pilot asked his radio operator to get in touch with Broome and

request help. The operator managed to send SOS signals… Outside his plane

Smirnoff saw the naked desert shore with mangro bushes in the tidal zone.

He ordered to unload water, food and three parachutes (in order to make

a shelter from the sun). Some of his passengers were wounded: Mrs. Van

Tuyn (twice in chest), mechanic – in both knees, the child – in both hands

and one of the KLM servicemen – Lieutenant Hendriks who was unconscious

in a very bad condition.

Their ordeal was becoming critical.

Smirnoff found the first-aid kit and gave the mechanic a needle. The wounded

child could not stop crying. They were desperately short of water and food,

and Smirnoff set up strict rationing for it. They stretched the parachutes

between chopped mangro branches. Then Smirnoff sent a KLM serviceman back

to the plane to pick up mail? Flying logbook and the parcel from the safe.

When he was getting off the plane a wave knocked the parcel out of his

hands. Smirnoff decided to look for it later.

Mrs. Van Tuyn died in the afternoon.

Smirnoff buried her in a shallow grave and read a funeral prayer in Russian.

Joop Blaauw died in the evening, at dawn next morning – Lieutenant Hendriks.

Smirnoff buried them, but soon was awakened but the noise of an aircraft

– it was a Japanese bomber approaching. It dropped two bombs on the Douglas

but they fell wide of the target. Later the plane (it was a Kavanashi flying

boat piloted by Lieutenant Shigeyashi Yamauchi) returned and threw two

more bombs which, fortunately, failed to explode.

The Russian pilot sent two Dutchmen

to search for water having ordered them to return by noon. Nevertheless,

they disobeyed and had returned only by sunset, covered by sunburns. On

the third morning 18-month old Johannes Van Tuyn died and was buried next

to his mother… Smirnoff and his mates assembled a primitive seawater freshener

out of rubber and copper piping from the plane and a kerosene burner and

tin. Anyway, it was producing insufficient amount of water.

The fourth morning changed nothing

in the condition of these people. Then Smirnoff divided the remaining water

between four Dutchmen Lieutenant Cramerus, radio operator Muller, sergeant-pilot

Brinkman and KLM serviceman Romondt said the following: "We have no choice

– you ought to go to Broom, otherwise we all are dead. Don’t come back!"

Smirnoff didn’t know that the nearest place where help could be found was

only in 10 kilometers to the north…

During the fifth night and the following

day Smirnoff kept himself busy looking after the seawater freshener, falling

asleep from time to time. Those who had left were not coming back and it

was giving hope that they had reached destination and the help was nearby.

The wounded mechanic died in the night… In the afternoon Smirnoff noticed

two dots on the horizon. Fearing they were Japanese planes he ordered his

exhausted men to scatter all over the beach and not to move. The planes

approached and he saw the RAAF markings on them. He stood up and began

to wave his hands, the same was done by other men. Having done ac circle

over them and lowering the altitude the planes parachuted several boxes

on the beach. The survivors leaped to them as wild animals and began to

tear them apart. The Russian pilot pulled out his revolver and shot into

the air – it stopped the depleted people: indeed, too a quick nourishment

might have ended dreadfully for them. Smirnoff let them drink a bit of

water, then again and only after that he allowed them to have some food.

The mood of the people rose, the hope was with them again and they even

threw the seawater freshener which saved their lives into the waves. They

didn’t know yet who had saved their lives…

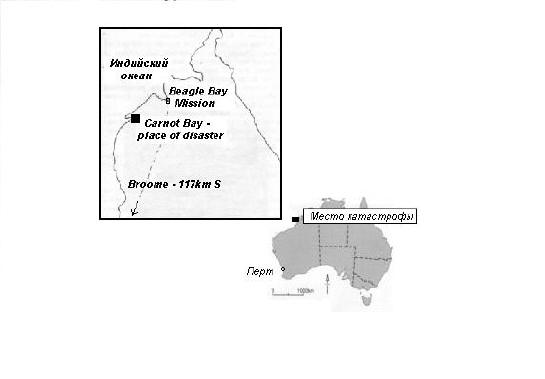

Several days after the disaster an

Aboriginal man Bernard George was on his way from Broome to the Beagle

Bay Mission when he noticed far away a plane resting on the shore. He had

known about the Japanese attack and understood that it was somehow related

to the bombardment. On 7 March upon arrival in the Mission he told a monk

Brother Richard and father Francis about it. It was reported to the local

military base commander Gus Clinch. In 45 minutes the help was ready –

water, food, medications, bandage, etc. All that was loaded on a mule.

Clinch himself and an Aboriginal Joe Bernard headed for help. One more

mule was loaded which was led by an Aboriginal Albert Kelly and monk Brother

Richard. On their way they came across the Dutchmen sent by Smirnoff to

Broom. They had lost their way and were on their way back to the crush

site. The monk gave them he first aid. He warmed up some water, softened

soap into paste and rubbed it into the sunburns of the Dutchmen. He gave

them water, then some food and sent with Albert to a cattle station which

was in about 13km away. Clinch ordered Joe to lead the mule to the crush

site, clarify the situation and come back…

Smirnoff woke up when the Aboriginal

leaned over him. He pulled out his revolver and pointed it at the newcomer

but that smiled. He said to the pilot: "You lie. Want some tea?" – "Nothing

could be better<" – Smirnoff replied. The Aboriginal man unloaded the

mule, found a kettle and wood chips, set a fire and boiled water. "Help

will come soon!" – he said and left with his mule.

Next day about midnight Clinch, Brother

Richard and Albert Kelly came to the camp. They smelled strong corpse stench

even before they approached the camp: the shallowly buried dead bodies

were decaying quickly in the humid heat… The way back to the mission took

them three long days.

Many people of Broome had also been

looking for the downed plane and casualties on their own vehicles. One

of the vehicles brought the mail from the crush site but there was no mysterious

parcel in it… Having thanked the missionaries and Aboriginals for assistance

Smirnoff and his comrades headed to Broome on a truck. Upon arrival they

were placed in a hospital for examination and cure for several days. In

a week the Russian pilot headed to Perth, and from there – to Melbourne.

Sydney was his destination as his wife had been already there.

During Smirnoff’s stay in Melbourne

he was visited by a police detective and a Commonwealth Bank serviceman.

Captain Smirnoff? – the serviceman

asked. – I am here to receive the parcel you had gotten before your departure

from Bandung.

- The parcel is missing, - Smirnoff

replied and told about everything happened. – What was in there? – he asked.

- Diamonds, thousands of high quality

diamonds…

… In March 1942 Frank Robinson and

James Mulgrue fearing new Japanese bombings decided to leave Broome on

a motorboat. Having bought food and fuel they left northwards. En route,

in a small bay, they met a man named Jack Palmer whose boat was anchored

in it. They sailed north along with him and came across a crush-landed

aircraft on the coast. Palmer and two Aboriginies he traveled with went

ashore in a small boat. There Palmer got on the plane and threw away various

things which the Aboriginies took for themselves. Between the pilot’s seat

and a small fuel tank (according to other sources – on the beach) he found

a wet brown parcel sealed by wax. He took the parcel to his motorboat and

opened it. Inside it he found a cigar box full of diamonds. Palmer picked

up the largest ones and tipped them into aluminum cups which he hid. He

wrapped the rest in a rag, moved to the Robinson’s and Mulgrue’s motorboat

and told them that he had found a bag of diamonds on the sand near the

plane. "Take a handful for each of yourself and don’t tell anybody about

this find," – he said.

Jack Palmer was going to join the army

and hoped that if he returned part of the diamonds to the authorities he

would get some privileges for it. Having selected small diamonds, he collected

them into two salt-cellars and on arrival to the Beagle Bay Mission went

to see the commander of the military base but found nobody there. He left

his motorboat in the Mission and flew to Perth on a passenger plane. There

he went to the district military commandant Major Gibson and told him about

the crush-landed plane and his find of a water-soaked parcel with diamonds

next to it. The Major had known already about the crushed plane and the

valuable parcel from an inquiry from the Commonwealth Bank.

An investigation began. It was revealed

that Palmer had taken "something" out of the plane, besides, pieces of

wrap paper, cord and wax were found on the beach. The story was told the

Aboriginies from the palmer’s boat, Robinson and Mulgrue did not try to

conceal the truth either. The latter had put his share of diamonds into

a film box and dug it into sand on the beach near Beagle Bay. The box had

been found by an Aboriginal woman wandering about the beach, and given

to the military base commander. Besides, people began to come across diamonds

in a variety of locations:-

- a Chinese trader had some

- amongst aboriginal communities

- in a matchbox in a train carriage

compartment

- in the fork of a tree (found after

the war)

- in a fireplace in a house in Broome

The investigation went on. On 12 April

1943 Robinson and Mulgrue were committed to trial. They were acquitted

of all charges as they had not committed any theft. Palmer was not sentenced

either as he had handed two salt-cellars with diamonds to the authorities.

It remained unproved that he had stolen part of diamonds. He returned to

Broome, joined the Army and became a lighthouse caretaker. After the war

he opened a food store, a motorboat moor, a house, a motorcycle and a car,

generally, began to live swell life. However, in 1950 the doctors discovered

that he had a stomach cancer. He was in the Broome hospital when a priest

Father MacKelson visited him. During their conversation he asked jack:

"What have you done with the rest of the diamonds?" – "I handed all of

tem to authorities," – Jack replied with a smile…

There had been 300 000 pounds worth

of diamonds in the parcel (prices of those times) and only worth of 21

777 was returned. The mystery of vanished diamonds which would be 10 million

US dollars worth nowadays was taken by Jack Palmer to his grave.

Captain Smirnoff eventually found

his wife in Sydney, then they moved to Brisbane. In 1943 he was summoned

to court in Perth where he gave his evidence. He was not accused of anything.

In 1944-1945 he worked as a pilot in the American Airway company, and in

1946 he a and his wife returned to Amsterdam (Holland). His wife Margo

died soon after that in 1947. Smirnoff kept flying till 1949 (on the

photo to the left – Smirnoff after the war) as a KLM pilot. According

to some sources he had a chance to visit his motherland during one of his

flights but he never got a permission to come to the USSR. After retirement

Smirnoff settled on the Majorca Island where he died on 28 October 1956.

He was buried there but later ( 20-11-1959) his ashes were re-buried in

Heemstede (some 40 km from Amsterdam) next to his wife’s grave. The place

of his crush-landing in Western Australia is still named the Smirnoff Beach.

Captain Smirnoff eventually found

his wife in Sydney, then they moved to Brisbane. In 1943 he was summoned

to court in Perth where he gave his evidence. He was not accused of anything.

In 1944-1945 he worked as a pilot in the American Airway company, and in

1946 he a and his wife returned to Amsterdam (Holland). His wife Margo

died soon after that in 1947. Smirnoff kept flying till 1949 (on the

photo to the left – Smirnoff after the war) as a KLM pilot. According

to some sources he had a chance to visit his motherland during one of his

flights but he never got a permission to come to the USSR. After retirement

Smirnoff settled on the Majorca Island where he died on 28 October 1956.

He was buried there but later ( 20-11-1959) his ashes were re-buried in

Heemstede (some 40 km from Amsterdam) next to his wife’s grave. The place

of his crush-landing in Western Australia is still named the Smirnoff Beach.

The life of this outstanding man and

brave pilot engulfed incredibly much. Perhaps, he may be considered as

a lucky man – he took part in the most dramatic events of the XX century.

His flying career was really unique – he spent 27 000 hours in the air!

He wrote two books: «Smirnoff Vertelt» («Smirnoff Tells»,

1938) and «De toekomst heeft vleugels» («The Future Has

Wings», 1947). His person attracted attention of Hollywood – in 1944

two cinema studios wrote scenarios about his life, but the Russian pilot

didn’t like them and he rejected the idea.

He became a legend. Nowadays, when,

many decades after, the names of the Russian heroes of WWI and émigrés

have returned to Russia, his motherland may be proud of the fact that he

is one of her most famous sons.

The original publication belongs

to George Kositsyn (the paper "Na Sopkakh Manchzhurii") and was first published

by him with the permission of "Hesperian Press" (Western Australia). The

web-page includes some additions and alterations.

Other web-sites about the life of Ivan

Smirnoff:

http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/smirnoff.htm

http://www.cableregina.com/users/magnusfamily/ww1rus.htm

http://www.wwiaviation.com/aces/ace_Smirnov.shtml

http://club.euronet.be/philippe.saintes/smirnov.htm

Back

to contents

Commander of a transport aircraft

DC3 (Douglas) of the Dutch Air Force Captain Ivan Vasilievich Smirnoff

(on the photo to the left – he during WWI) became an unwilling participant

of this episode. He was born on 30 January 1895 on a farm near the town

of Vladimir (Russia) in the family of a well-off peasant cattle greaser

and wheat grower. Ivan was interested in mechanics from an early age, liked

to maintain and repair agricultural machinery which belonged to his family.

His father wanted him to enter the Moscow University to study engineering,

but, when the WWI had broken out Ivan escaped to the front with two mates,

joined the army voluntarily and was enlisted into the 96th Omsk

regiment. He distinguished himself in the infantry and at the age of 19

was awarded with the St George Cross. After being wounded into the leg

he got his bone damaged to the point when the surgeons wanted to amputate

his leg, but he refused and was placed into a hospital situated next to

an airfield. After recovery from the wound he applied for acceptance to

the aviation school, finished it and was accepted in the 19th

squadron led by the most famous Russian ace of the WWI – shtabs-kapitan

(staff-captain) Alexander Kazakov. Smirnoff shot down 12 German aircraft

(the last – on 10 November 1917)? And as to the number of battle awards

had become the second in the Russian Imperial Air Fleet. Amongst his awards

(beside the Soldier’s St George Cross) there were the Officer’s St George

Cross, Gold Saber, Orders of St Anne, St Stanislaus, St Vladimir with Swords,

White Eagle. In 1917 together with his friend Login Lirsky Smirnoff fled

to England where he joined the RAF. He, a former ensign of the Russian

Army, served here as a flying instructor in the rank of major. After the

Armistice he was demobilized and during the Civil War in Russia he served

as the White Army General Denikin’s attaché in France.

Commander of a transport aircraft

DC3 (Douglas) of the Dutch Air Force Captain Ivan Vasilievich Smirnoff

(on the photo to the left – he during WWI) became an unwilling participant

of this episode. He was born on 30 January 1895 on a farm near the town

of Vladimir (Russia) in the family of a well-off peasant cattle greaser

and wheat grower. Ivan was interested in mechanics from an early age, liked

to maintain and repair agricultural machinery which belonged to his family.

His father wanted him to enter the Moscow University to study engineering,

but, when the WWI had broken out Ivan escaped to the front with two mates,

joined the army voluntarily and was enlisted into the 96th Omsk

regiment. He distinguished himself in the infantry and at the age of 19

was awarded with the St George Cross. After being wounded into the leg

he got his bone damaged to the point when the surgeons wanted to amputate

his leg, but he refused and was placed into a hospital situated next to

an airfield. After recovery from the wound he applied for acceptance to

the aviation school, finished it and was accepted in the 19th

squadron led by the most famous Russian ace of the WWI – shtabs-kapitan

(staff-captain) Alexander Kazakov. Smirnoff shot down 12 German aircraft

(the last – on 10 November 1917)? And as to the number of battle awards

had become the second in the Russian Imperial Air Fleet. Amongst his awards

(beside the Soldier’s St George Cross) there were the Officer’s St George

Cross, Gold Saber, Orders of St Anne, St Stanislaus, St Vladimir with Swords,

White Eagle. In 1917 together with his friend Login Lirsky Smirnoff fled

to England where he joined the RAF. He, a former ensign of the Russian

Army, served here as a flying instructor in the rank of major. After the

Armistice he was demobilized and during the Civil War in Russia he served

as the White Army General Denikin’s attaché in France.